Robert Schumann’s Dichterliebe op. 48 (1840) is among the most popular song cycles of the classical music canon. For singers and pianists, performing it with the highest of artistic sensibilities and skill is considered a ‘holy grail’. There is at present a tacit assumption that we in the 21st century have inherited knowledge of stylistically appropriate ways to interpret music of the Romantic era. But is that really true? How did Schumann expect Dichterliebe to sound, and what was the sonic effect of the cycle at its first public performance in 1861 by Julius Stockhausen (1826–1906) and Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)? Can this sonic information be reimagined from Schumann’s notation?

To answer these questions, we can turn to compelling evidence preserved on early sound recordings made at the turn of the 20th century. These historical recordings (wax, electrical, and reproducing piano rolls)—which constitute veritable time capsules—reveal that singers and pianists from or connected with Schumann’s circle (and others besides) employed a range of un-notated expressive practices to underscore the text, and literally to ‘speak’ through singing and piano playing. Many of these practices became outlawed or were forgotten during the 20th century. As a result, today’s expectations for the performance of Dichterliebe do not align with the performance practices of Schumann and his circle.

The Rise of 20th-Century Modern Style

The first half of the 20th century saw unprecedented changes in performance style (already heralded in the late 19th century), implementing modern aesthetic qualities of literalness, neatness, precision, and stability in realising the composers’ score. Modern musicians increasingly judged ‘Romantic’ expressivity as overly sentimental, lacking control, and contravening composers’ score indications, overlooking or ignoring the centrality of the 19th-century concept of schöner Vortrag (beautiful performance). Schöner Vortrag promoted the primacy of individual artistic input in breathing life into the ‘lifeless’ notes of the score. The new modern style eschewed previously valued practices in singing and piano playing, many of which were part of a continuum of practice extending back to the 18th century or earlier.

As the 19th century progressed, increasingly powerful pianos and orchestras, as well as concert venues of growing size, led singers to experiment with a new technique based principally on increasing the length of the vocal tract (including lowering of the larynx) to create extra resonance and carrying power when needed. But as time went on, this new technique came to dominate. Its constant use resulted in a preponderance of darker vowels (resulting to a homogenous monochromatic timbre), and a wider, often slower, and more continuous vibrato (pitch undulation) regardless of the emotional qualities of text and music. These developments—arguably the most radical changes in singing ever heard—eventually caused the weakening of connection between speech and singing.

Historically Informed Performance (HIP)

The underlying concept of HIP—that the composer’s expressive objectives should be considered in the performance of their compositions—was already extolled by theorists as early as the 18th century, and some musicians experimented with the use of historical instruments for concerts of ‘historical’ music. But, from the 1960s, interest in HIP accelerated to an unprecedented level, supported by the recording industry. A driving force was the wider adoption of ‘period’ or historical instruments (including pianos), fundamentally changing the sound of instrumental ensembles for pre-modern music in quite remarkable ways. HIP also developed methods to translate performance practice information in pedagogical sources literally into sound. This effect, too, added a vital dimension in the recovery of the sound world of historical eras, however, without audible evidence of those eras it is impossible to know if the process has been successful.

In the last few decades, early sound recordings have become increasingly the focus of performance practice research. The earliest known singers on record, Peter Schram (1819–1895), Jean-Baptiste Faure (1830–1914), Gustav Walter (1834–1910), Charles Santley (1834–1922), Marianne Brandt (1842–1921), Adelina Patti (1843–1919), Edward Lloyd (1845–1927), Victor Maurel (1848–1923) and Hermann Winkelmann (1849–1912), and pianists Carl Reinecke (1824– 1910), Theodore Leschetizky (1830–1915), Camille Saint-Saëns (1835–1921), Johannes Brahms (1833–1897), and many other anonymous pianists accompanying singers of the era, began their musical training around the mid 19th century. We can assume with confidence that their performance practices, which sound strikingly different to modern ones, are reflective of those dominant in the decades surrounding the composition of Schumann’s Dichterliebe. Significantly, too, these musicians’ recordings reveal practices that were not discussed in contemporaneous written sources, perhaps due to lack of scope or because the finer nuances of expressive effect could not adequately be described in words. And sometimes, their performances appear to contradict their own verbal instructions; it is evident that such instructions were: intended for a specific occasion only; directed specifically at non-professional musicians; or, not intended to be taken literally. For the era stretching back to Schumann, early recordings are an audible key to ‘deciphering’ the hidden meaning of written advice and composers’ notational practices.

Dichterliebe Reimagined

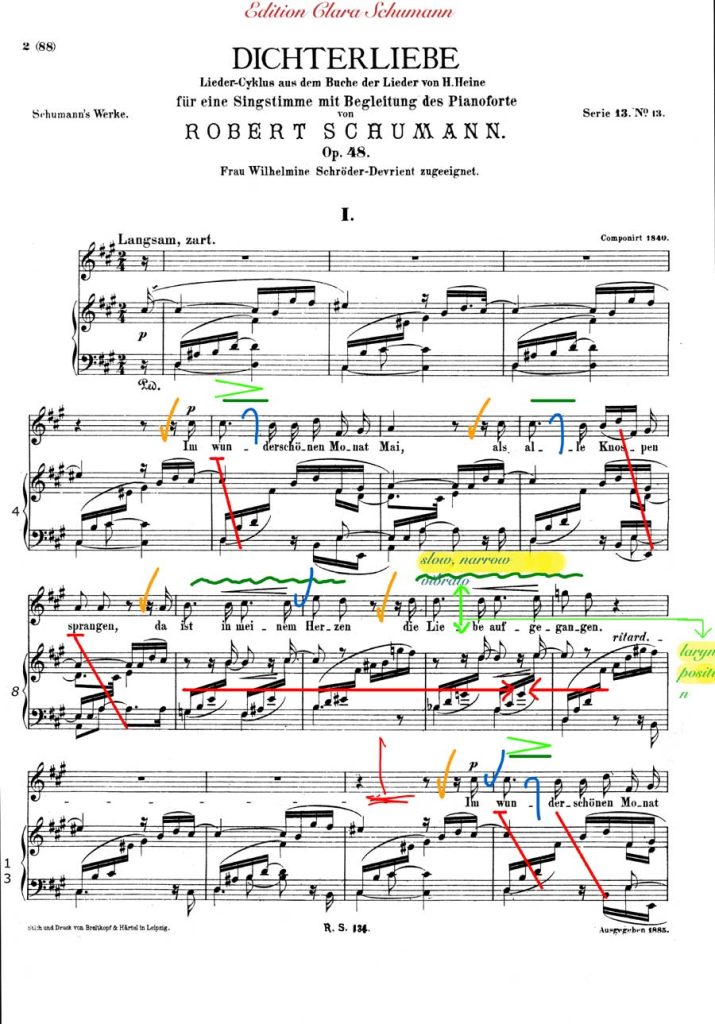

Our recording of Dichterliebe is the result of several years of detailed study, building on existing HIP research. We derived new knowledge from analysis of a very large body of early recordings and written sources that spurred the use of a wider range of 19th-century techniques and expressive effects than has been the case until now. In terms of singing, it encouraged a more flexible approach to larynx positions as heard on the recordings and extolled in 19th-century pedagogical sources such as Manuel García’s (1805–1906) influential singing method first published in 1840. Singing with higher larynx positions, as opposed to the constantly lowered (default) larynx position – an imperative in modern singing, aids in achievingmyriad speech-like tonal effects, greatly enhancing text clarity. These types of effects are particularly noticeable, for example, in the intimate moments of the songs IV “Wenn ich in deine Augen seh”, X “Hör’ ich das Liedchen klingen” and XII “Am leuchtenden Sommermorgen”. Additionally, we have adopted bonafide 19th-century performance practices applied ornamentally (sometimes in seemingly unusual or unorthodox ways). In singing, these include varied forms of portamento (the audible sliding between adjacent notes), messa di voce (a crescendo-decrescendo effect) and numerous other dynamic shapes for single notes, and avoidance of strictly non-vibrato singing, which sources show was employed only sparingly during the 19th century, as a special effect. In piano playing, the adoption of un-notated chordal arpeggiation and manual asynchrony (separating melody from accompaniment) to enhance expression, colour, and texture, and for special emphasis; agogic accentuation (accent by length), was paramount to enhancing the text imaginatively, and as an essential aid in responding artistically to the aforementioned vocal practices. Perhaps most importantly, in both singing and piano playing, we have incorporated various styles of tempo rubato (rhythmic asynchrony and noticeable rhythm and tempo flexibility), to achieve a rhetorical style, imbuing our interpretation with the improvisatory spirit of the early recordings. Rhythmic asynchrony (between voice and piano), following the declamatory rhythm of the German, for example, can be heard throughout songs X and XII.

In the piano part of song X, Schumann’s way of notating the main melody notes (using double stemming) in a delayed manner, creating asynchrony with the bass, enhances the deeply melancholic atmosphere expressing the suffering of the protagonist. We have extended the use of asynchrony into the vocal line. This conjures the effect that the protagonist is choked up and finding it hard to say the words. In song XII again, Schumann introduces asynchrony in the piano part. Similarly, we continue this in the vocal line to extend Schumann’s magical, dream-like atmosphere evoked by the words “The flowers whisper and speak.” In song IX “Das ist ein Flöten und Geigen”, a special dynamic effect created by several quickly repeated messe di voce on single notes helped to vivify words on single notes, for example in bars 7 and 45: Geigen (fiddling) and Dröhnen (roaring). Similarly, in song XIII “Ich hab’ im Traum geweinet”, bar 26: geweinet (cried); and song XVI, bar 50: Schmerz (pain).

We have transposed several songs based on the common practice in Schumann’s time as a means to accommodate individual singers’ ranges. In order to create successful harmonic transitions into foreign keys resulting from such transpositions, short piano improvisations were interpolated between songs VII-VIII-IX. This too, was standard practice. In 1888, for example, the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik reported that Carl Reinecke—who Schumann claimed was one of few musicians who understood his music—delighted the audience with his Dichterliebe accompaniment, which included a dozen transitions or short connections.

These and other practices were part of the 19th-century performer’s expressive palette, heard abundantly and with great artistic flair on early recordings. Listen for example to how Pelagie Greeff-Andriessen (1860–1937) spontaneously changes rhythms on her 1901 recording of “Ich grolle nicht”. Astonishingly, she delays, her first entry, thus creating incredible suspense. In bar 19, she uses anticipation by coming in early, with the effect of confidently affirming the phrase “Ich grolle nicht” (I bear no grudge).

Equally astonishing is the use of tempo modification and rhythmic asynchrony by Robert Blass (1867–1930) and his pianist on their 1903 recording of “Im wunderschönen Monat Mai” and “Ich grolle nicht”, again strongly heightening text expression. Even as late as 1935, extraordinary speech-like effects can be heard on Charles Panzera’s (1896–1976) and Alfred Cortot’s (1877–1962) Dichterliebe recording. Panzera annunciates the text very clearly and places syllables freely to make them come out in the texture.

Other Dichterliebe recordings opened our ears to the colourful diversity of 19th-century expressive practices. These include Therese Behr-Schnabel’s (1876–1959) recording of “Ich grolle nicht” and Richard Tauber’s (1891–1948) “Aus meinen Tränen spriessen”, from 1904 and 1921 respectively. On these recordings, both singers and their pianists apply tempo modification in a manner that goes beyond anything we could have imagined, again strongly enhancing the expression of the poetry. On her 1907 recording of “Ich grolle nicht”, Elena Gerhardt (1883–1961) similarly uses tempo modification to extraordinary fashion. Additionally, she applies strong dynamic variation. Listen for example to her expressive crescendo starting in bar 23 that builds towards “Und sah die Schlang’, die dir am Herzen frißt” (And saw the serpent gnawing at your heart). Jeanne Gerville-Réache (1882–1915), on her 1911 recording of “Ich grolle nicht” colours this same dramatic phrase, noticeably widening her vibrato. Of great interest too, is George Henschel’s (1850–1934) recording of this piece from 1928. It is astonishing hearing Henschel accompany himself, while still being able to use rhythmic asynchrony. Henschel’s introspective approach contrasts strongly with most other recordings.

In preparing our Dichterliebe, we engaged with innovative practice-led methods such as emulation (close imitation) and embodiment of historical recordings to realign our performance aesthetics with pre-modern ideals, before using cyclical research methods (back and forth comparison between written sources and practical experiments) to extrapolate styles and practices likely to have predominated in Schumann’s lifetime. These methods have greatly assisted us to deliver the narrative in each of Dichterliebe’s songs in rhetorically-aligned ways (speaking through singing and piano playing) to offer fresh perspectives for practitioners and audiences today.

Annotated score of Dichterliebe